Cenote History

The history of cenotes began around 2.8 million years ago when the Yucatán peninsula rose from the sea to create a 2.5 km/1.6 mi thick porous limestone bedrock. This is why you see a variety of coral reef fossils in the caverns & caves.

Cenotes are formed through a process called chemical weathering, which involves the slow dissolution of limestone by slightly acidic rainwater. Rainwater becomes acidic when it interacts with CO2 in the atmosphere, forming carbonic acid. This weak acid dissolves the calcium carbonate (CaCO3) present in the limestone, creating underground channels. Dissolved limestone forms a calcium carbonate solution in water, and this solution drips into the dry passages and solidifies, creating speleothems (stalactites, stalagmites, columns, flow stones etc.). Over time, the continuous dissolution of limestone enlarged these channels, creating extensive networks of underground caves. While passages continued to grow, the ceiling rock thinned, making it unable to support its own weight and eventually collapsed inward, resulting in cenotes.

Cenote comes from the Mayan word, d’zonot, which translates to ‘cavern with water’. The Maya consider cenotes to be sacred, containing portals to Xibalbá - the Maya underworld.

The Different Cenote Types

Open

Semi-Open

Cave

A halocline (from Greek hals, halos ‘salt’ and klinein ‘to lean’) is a distinct vertical layer in a body of water where fresh and saltwater meet. Saltwater, which is more dense and a degree or two warmer, sinks below the freshwater,

creating two obvious layers.

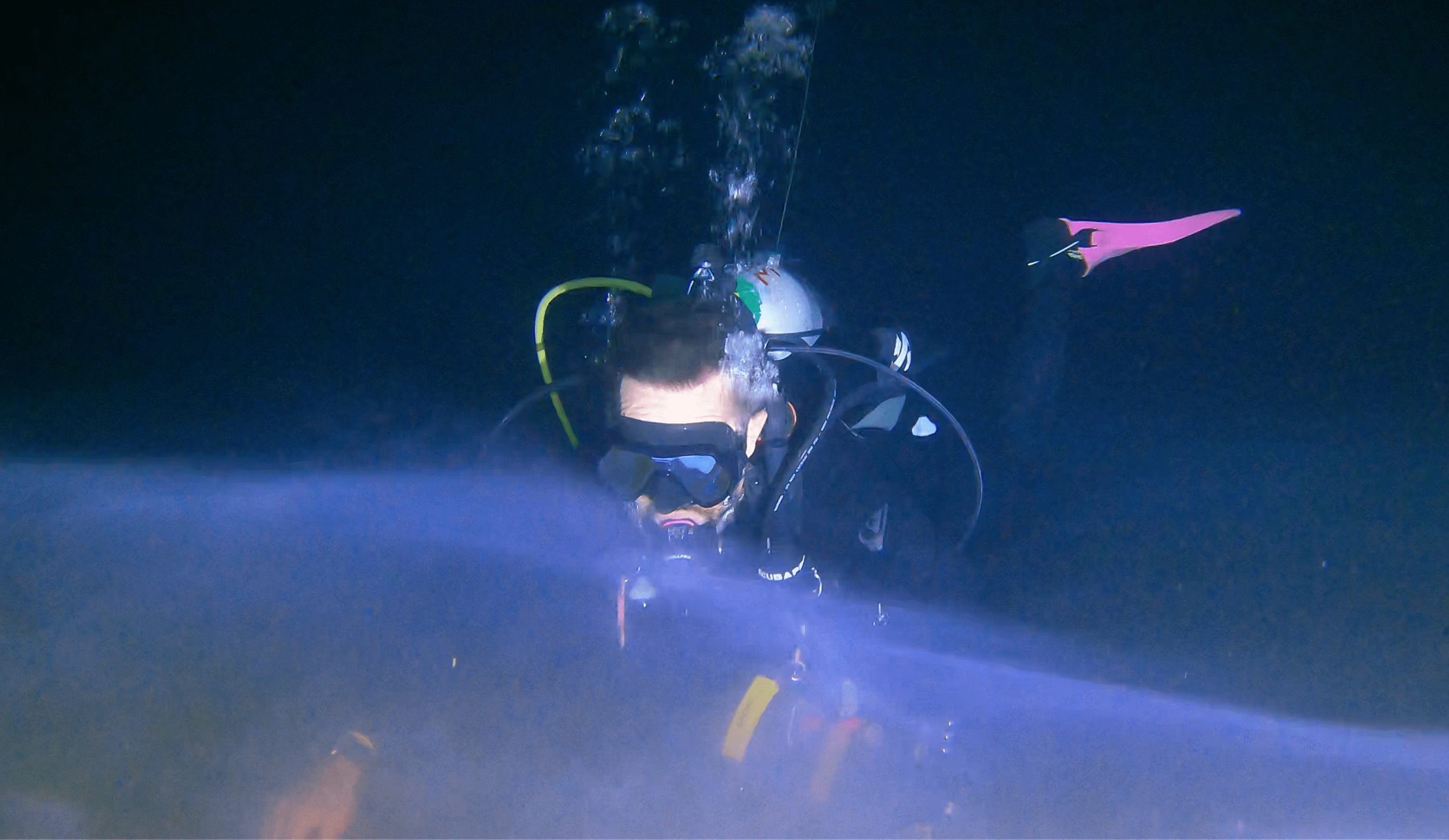

Light passing through a halocline will refract, resulting in visual distortions and oily-looking water. Everything will appear blurry when swimming behind someone passing through a halocline, it’s quite the psychedelic experience. When untouched, the halocline looks like the mirrored surface of a flat lake; it’s super trippy! Try moving your hand around the undisturbed halocline and watch the water turn blurry.

The photos below are examples of halocline.

Halocline

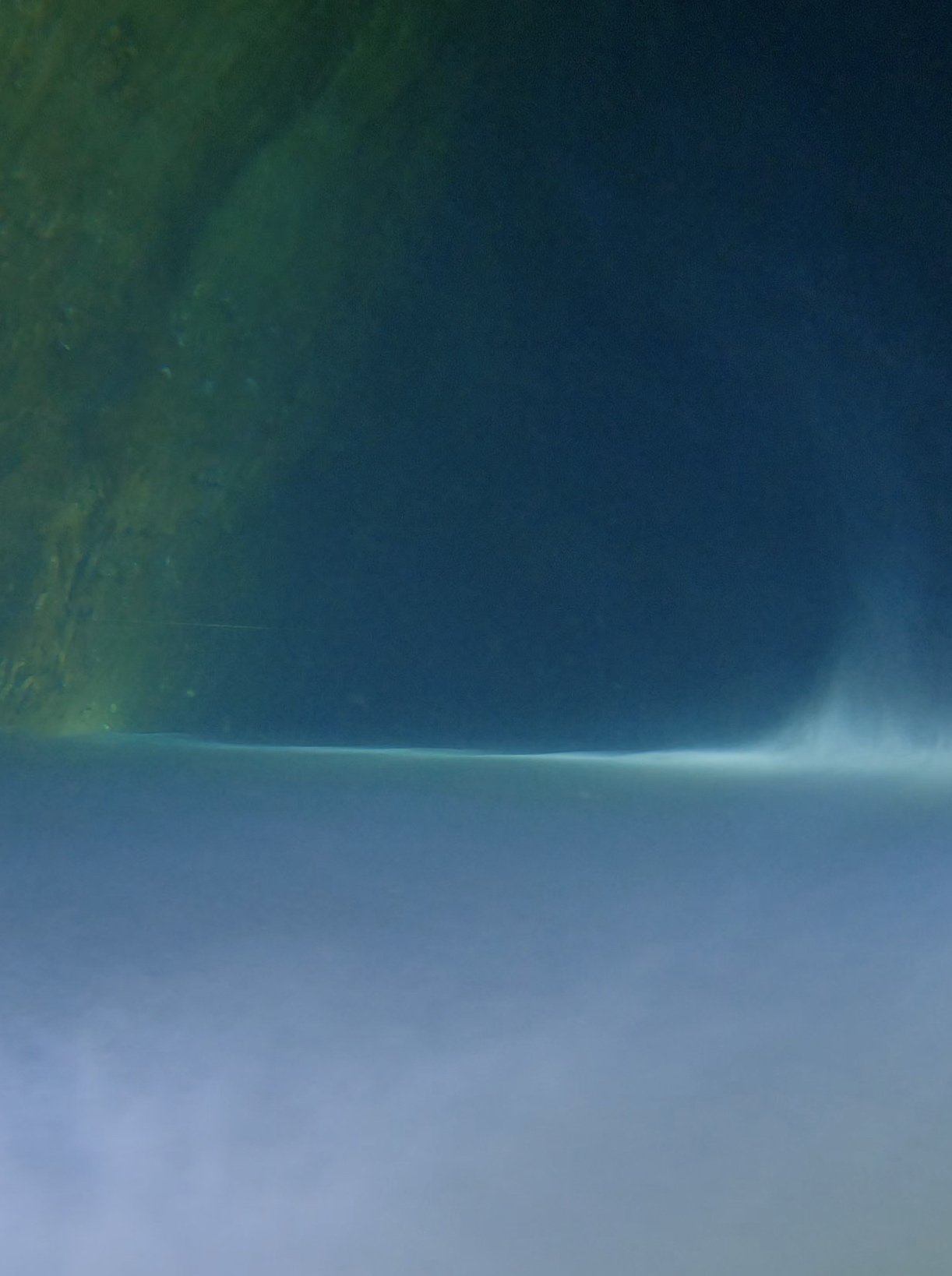

Hydrogen Sulfide Clouds

A dense gas created by the decomposition of organic material. Because of its density, hydrogen sulfide floats on salt water and sinks into fresh water. We limit our exposure to this toxic gas as it can cause eye irritation and smells like rotten eggs. Always make sure you have a proper seal on your mask and keep your reg in your mouth while descending into the cloud.

The photos below are examples of hydrogen sulfide.

Mayan Mythology & the Sacred Cenotes: Dive into the Ancient World

Beyond their breathtaking beauty, cenotes hold profound spiritual and cultural significance for the ancient Maya, offering a unique opportunity to connect with a rich history spanning millennia. Join us as we explore the captivating mythology surrounding these natural wonders, understanding why they were considered sacred gateways to another realm.

The Cenote: A Lifeline and a Sacred Gateway

For the ancient Maya, cenotes (from the Yucatec Maya word ts'onot, meaning "sacred well") were far more than just sources of fresh water in a region devoid of rivers. They were:

Vital for Survival: Providing the sole access to water for drinking, agriculture, and daily life, cenotes dictated the location and prosperity of major Mayan cities, including Chichen Itza and Mayapan.

Centers of Community: They served as gathering places, fostering social interaction and acting as economic hubs where goods and ideas were exchanged.

The Heart of the World: Deeply integrated into Mayan cosmology, cenotes were believed to be the umbilical cord connecting the surface world to the underworld, Xibalba. Their constant flow of water symbolized life, death, and rebirth.

Deities of the Deep: Who Resided in the Cenotes?

The watery depths of the cenotes were believed to be the domain of powerful deities and spirits, reflecting the Maya's reverence for water and its life-giving properties:

Chaac (The Rain God): The most prominent deity associated with cenotes, Chaac was crucial for the agricultural prosperity of the Maya. Offerings were made to him to ensure timely rains and abundant harvests. He is often depicted with a long nose, fangs, and carrying an axe or serpent.

Water Lily Serpent: A significant mythological creature, the Water Lily Serpent was closely linked to water, fertility, and creation, often found in iconography related to sacred water sources.

Chac Chel: Sometimes depicted as an elderly goddess associated with water, weaving, and childbirth, she also held sway over aspects of the watery realm.

Chac Mool: While not a deity himself, the Chac Mool statues found near cenotes (often with a bowl on their stomach) were believed to be intermediaries between humans and the gods, receiving offerings intended for the deities of the underworld.

Kukulkaan (Feathered Serpent God): In some myths, Kukulkaan, a major deity, was also associated with controlling droughts, further linking him to the precious water found in cenotes.

Aluxes: Mischievous forest and field spirits, akin to goblins or elves, were also believed to inhabit cenotes, acting as guardians of the natural world.

Xibalba: The Underworld Portal

Perhaps the most significant mythological aspect of cenotes was their role as direct portals to Xibalbá, the terrifying yet fascinating Mayan underworld.

Journey of the Soul: For the Maya, Xibalba was not a hellish place of eternal damnation, but rather a realm of transition and transformation. Souls of the deceased, particularly those who died violently or were sacrificed, were believed to enter Xibalbá through cenotes.

Realm of the Lords of Death: Xibalba was ruled by the formidable Lords of Death, including Hun-Came ("One Death") and Vucub-Came ("Seven Death"). The journey through Xibalba was fraught with trials and challenges for both gods and mortals.

Blurring of Worlds: The dark, still waters and echoing caverns of cenotes enhanced their perception as liminal spaces where the veil between the earthly realm and the supernatural was thin.

Rituals, Offerings, and Sacrifice

The profound spiritual significance of cenotes led the Maya to perform elaborate rituals, ceremonies, and offerings within and around them. These practices served various purposes, including appeasing the gods, ensuring fertility, seeking guidance, and maintaining cosmic balance.

Human Sacrifice: Archaeological evidence, particularly from Cenote Sagrado at Chichen Itza, confirms that human sacrifices were a prominent part of these rituals. Victims, often young men, women, and children, were cast into the cenote, sometimes after being drugged with hallucinogens. Analysis of remains from the chultún (a modified cave or cistern) near Mayapan even suggests that male and possibly twin sacrifices occurred, echoing the Hero Twins myth.

Precious Offerings: Alongside human sacrifices, the Maya offered valuable artifacts to the cenote deities. These included:

Jade: Highly prized, jade artifacts like pendants, beads, and figurines were symbols of water, fertility, and life.

Gold and Copper: Ornaments, bells, and other precious metal objects, often originating from distant lands, highlight the extensive trade networks of the Maya.

Pottery and Ceramics: Intact or intentionally broken vessels, sometimes filled with other offerings.

Copal Incense: Burned during ceremonies, the smoke of copal was believed to carry prayers and offerings to the gods.

Perishable Organic Materials: While less preserved, evidence suggests offerings of rubber, wood, textiles, and food items were also common.

Intentional Damage: Many artifacts recovered from cenotes show signs of intentional breakage or "killing" before being deposited. This act was believed to release the object's spirit or make it usable in the spiritual realm.

Purpose of Rituals: These offerings and sacrifices were performed to:

Secure good harvests and rain.

Seek divine intervention or prophecy.

Honor ancestors and maintain cosmic order.

Commemorate significant events.

Myths, Legends, and Their Echoes in the Cenotes

Cenotes feature prominently in some of the most enduring Mayan myths and legends:

The Popol Vuh and the Hero Twins: The Mayan creation epic, the Popol Vuh, tells the story of the Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, who descend into Xibalba to avenge their father's death and defeat the Lords of Death. Their journey through the underworld, involving trials and transformations, mirrors the spiritual journey associated with cenotes. The discovery of twin burials in a chultún adds an intriguing archaeological link to this foundational myth.

Aluxes: Legends persist of the mischievous Aluxes who guard cenotes and other sacred natural sites. They are said to be invisible but can manifest to protect their domain or play tricks on travelers.

Chac Mool Rebirth: Some legends say that the Chac Mool statues, if placed correctly, could be reborn as jaguars, reflecting the Mayan reverence for this powerful animal and its association with the underworld.

Kukulkaan and Drought: Stories of Kukulkaan's power over drought reinforce the idea that offerings in cenotes were vital to appease the gods and ensure the continuation of life-giving water.

Archaeological Insights: Unearthing the Past

Archaeological investigations of cenotes have provided invaluable insights into Mayan mythological practices, directly corroborating ancient texts and oral traditions.

The Sacred Cenote at Chichen Itza: This famous cenote has been extensively explored, yielding a wealth of artifacts and human remains from the Classic to Postclassic periods (roughly 600-1500 CE). Divers have recovered:

Over 120 sets of human remains, with analysis indicating that victims were often young, both male and female. Some show signs of trauma consistent with ritual sacrifice.

Thousands of artifacts, including exquisite jade, gold, copper, pottery, and fragments of textiles and wooden objects.

Evidence of intentional breakage and "killing" of artifacts, consistent with their ritual deposition.

The Chultún Burials: Discoveries of burials in chultunes, sometimes considered artificial cenotes, like those near Mayapan, have provided further evidence of ritual sacrifice, including the possibility of twin sacrifices, which directly relates to the Hero Twins myth. These findings help us understand the complex funerary and sacrificial practices.

Symbolic Meaning: Mirrors of the Cosmos

Beyond their practical use, cenotes held deep symbolic meaning within the Mayan worldview:

Axis Mundi: They were seen as a sacred axis mundi, a central point connecting the three realms of the Mayan cosmos: the heavens above, the earthly plane, and the underworld below.

Life, Death, and Renewal: The constant flow of water, emerging from the earth and often flowing into underground rivers, symbolized the continuous cycle of life, death, and regeneration.

Cosmic Womb: Cenotes were sometimes viewed as a "cosmic womb," a place of creation and rebirth, from which life emerged and to which it returned.

Artistic Representation: Cenotes were often depicted in Mayan art and iconography, sometimes symbolized by the gaping jaws of a centipede or a serpent, representing their connection to the underworld.

The Cycle of Existence

Cenotes played a crucial role in Mayan beliefs about creation, the continuation of life, and the passage from death to rebirth:

Entry to the Afterlife: They were the primary entry point for the deceased into the underworld of Xibalba, where their souls would embark on a transformative journey.

Royal Rebirth: For kings and elite individuals, the journey through the underworld was often depicted as a path to rebirth and ascension into the Sky World, where they would join the gods and ancestors.

Perpetual Flow: The perpetual flow of water in cenotes mirrored the Mayan understanding of time and existence as cyclical, with death being a necessary part of the cycle of renewal.

I honor the profound spiritual heritage of these incredible natural formations. When you dive with me, you're not just exploring a beautiful cave; you're stepping into a living myth, connecting with the ancient heartbeat of the Maya.

Conservation

Each cenote is a fragile ecosystem. Cenotes support numerous life forms, including mammals, birds, reptiles, insects and various plants.

It is our duty to help protect and preserve these unique environments. Do not use mosquito repellent, sunscreen, or oils of any kind.

Cave formations, unlike reef coral formations, are not self-rejuvenating. Once damaged or broken, they are lost forever. Leave the cenote as you found it or better. Take only memories with you, kill only time, and leave nothing but bubbles.

I invite you to read this article from InDepth Magazine that discusses the importance of preserving cenotes.